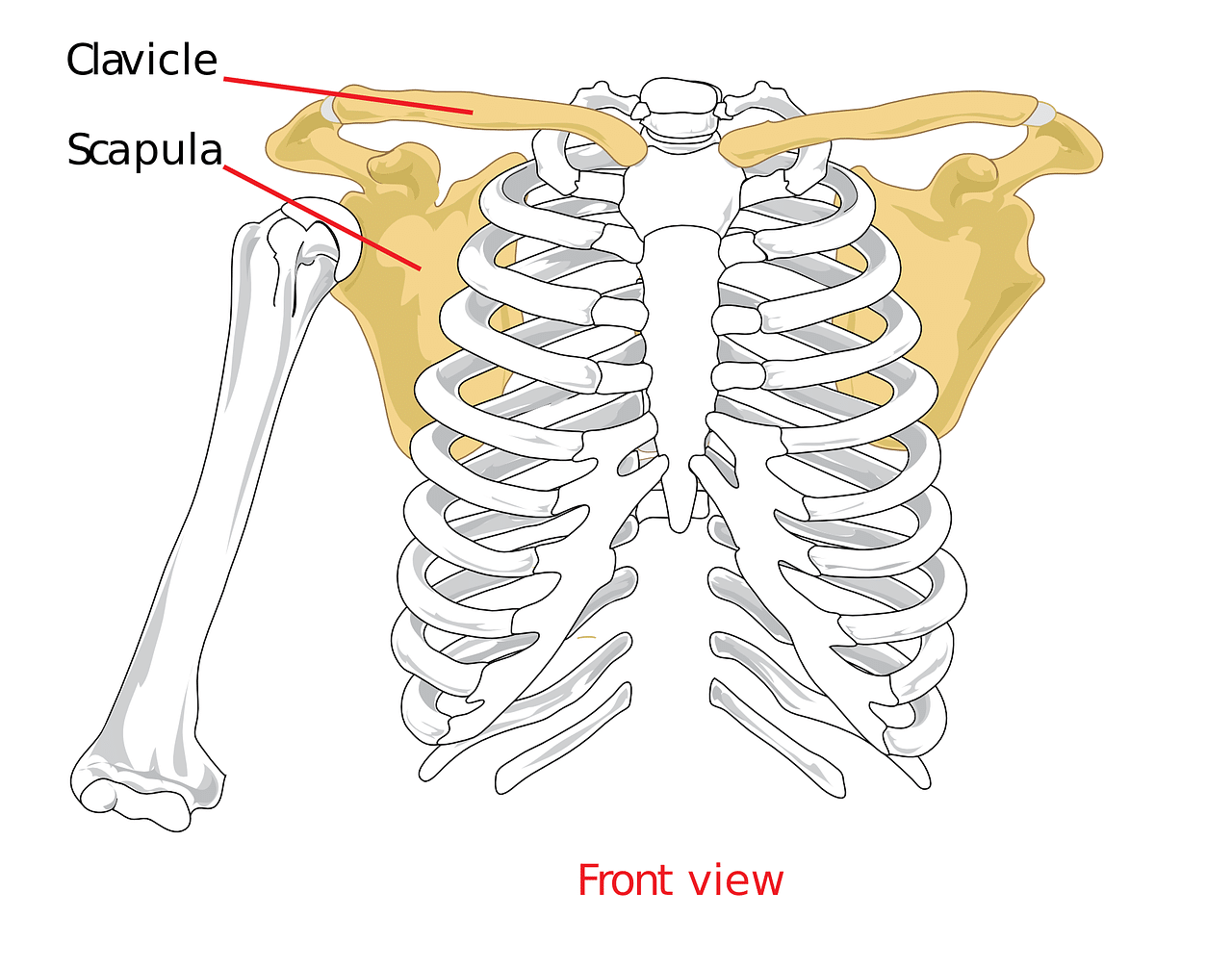

If you are a serious lifter, someone who trains consistently for years and progressively tries to get stronger and more muscular, then the odds are very high you will deal with a shoulder or pec strain at some point. There are those individuals who seemingly have injury proof chest and shoulders, but they are few and far between. Exceptions do not make rules or recommendations. For everyone else, taking care of your joint and tissue health MUST be factored into your training on a daily basis. Maintaining chest and shoulder health requires some anatomical knowledge, but its the application and practice that matter most. That said, a quick anatomy rundown is worth covering Why are the Shoulder and Pec prone to Injury? The Shoulder is injured far more than the pec, so lets start with that first. The shoulder is a “ball and socket joint”, but what does that mean? Relative to the shoulder, there is no actual “socket” the head of the humerus (arm bone) fits into. The humerus is attached entirely by muscle and tendons to the joint. Unlike the hip joint, there is no real “socket”, only a lot of muscular attachment points. You could visualize the shoulder joint as being more a “spoked” joint with multiple lines of muscle and tendon connecting it to the shoulder.

1. Maintain flexibility – When I say flexibility, I mean flexibility. How flexible is your chest? Can you put your hands behind your head comfortably? Can you raise your arms overhead? Can you stretch your chest without feeling like your shoulder is going to tear out? Your passive flexibility is the best indicator of your active range of motion (mobility). If you lose flexibility in the chest and shoulders, your long-term joint health and muscle health will suffer.

2. Train all angles of movement – Your shoulders can press overhead, at an angle, and perform front, lateral, and posterior deltoid raises. Your chest can press on a decline, forward, and a diagonal. If you can do perform dips, pushups, flat and incline presses, and overhead press, your shoulder health should be excellent. If you lose any of these ranges of movement, the others will gradually follow.

4. Strengthen the upper back. Your upper back muscles are the platform to do any kind of pressing movement from. They also move your shoulder blades, and shoulder blade movement is directly tied to rotator cuff health. Perform pulldowns, diagonal pulldowns and rows, and shrugs to strengthen your traps, rhomboids, and teres major and minor.

5. Always hydrate – I make this point often, but its needs to be repeated. Training with “dry” dehydrated muscles is a set up for a strain or tear. Always adequately hydrate by drinking water and electrolytes before training. I prefer electrolye packets or tablets in a liter of water.

6. Intelligently sequence your pressing workouts. Modify your training as you age so you maximally stimulate muscle tissue and minimally stress your joints. Start all pressing workouts with band pull aparts and an upper back row. Make your first pressing exercise an activation movement with a controlled range of motion. Put your heavy work third or fourth, after you’ve fully pumped your upper back, chest, and shoulder with blood. Stretch after your working sets are finished

7. Avoid movements that hurt-This is an obvious one, but often ignored. If a movement bothers your joints no matter how much you modify it, DONT DO IT. There is no good reason to persist in doing an exercise if it breaks you down more than it builds you up.

8. Drop the ego-Your strength will decline as you age. Your muscle mass will NOT though if you smartly train for hypertrophy and keep your reps moderate to high and weights reasonable.